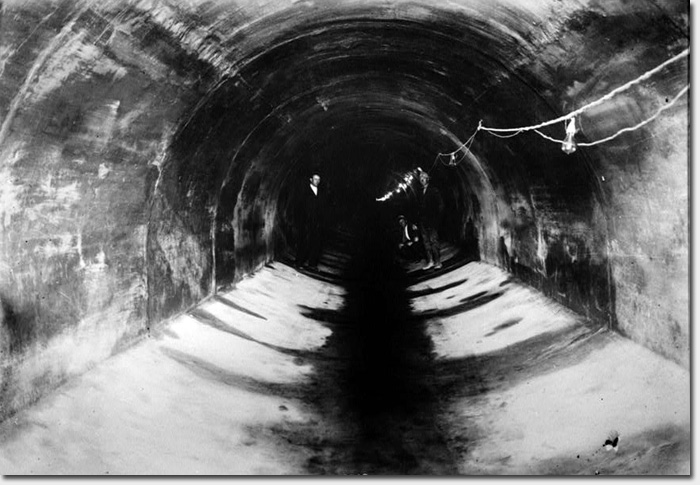

The interior of Mile Rock Tunnel just before it went into operation. August 1915.

Following the 1906 earthquake, San Francisco worked to rebuild itself. After being left high, and literally dry with a shortage of water during the quake, there was renewed interest and investment in the city municipal works, in particular a modern water system.

Even earlier, by the late 1890’s, San Francisco was growing quickly and the demand for a long-range design and plan for a city-wide sewer system was sought. The heavily populated areas of the city, like downtown, were already heavily sewered. Extensions were needed to handle the burgeoning population, which also meant more outfalls for the sewage were needed. At the time, the ocean was identified as one of the least harmful and offensive solutions.

Municipal engineers also proposed at the time that a combined system of storm water and sewage drains would decrease the total number of conduits needed and also serve to “flush out” the sewer lines with comparatively clean storm water run-off.

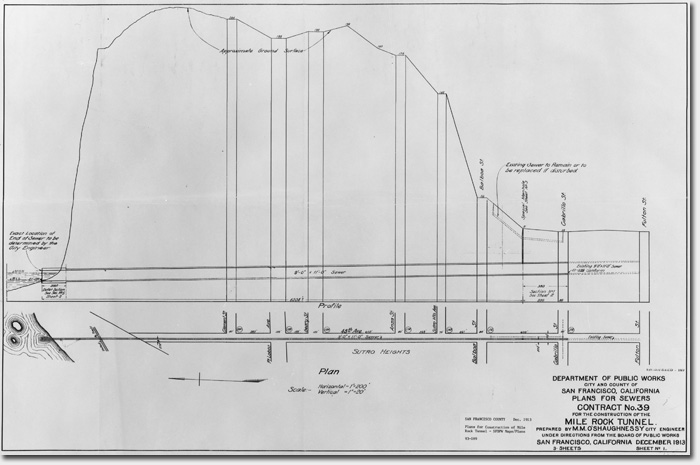

A 1908 sewer bond eventually provided the funding for Mile Rock Tunnel, an outfall tunnel constructed in 1914 and 1915. The tunnel was designed as a storm drainage facility for the Sunset and West Mission districts and portions of the Richmond and Ingleside districts.

The tunnel, which still exists today, is 4,233 feet long and as deep as 300 feet underground in some places. It begins at 48th Avenue and Cabrillo and ends at the San Francisco Bay in the vicinity of Mile Rock Beach.

When originally constructed, the tunnel was 9 feet high and 11 feet wide – large enough to drive a car through (more on that later). The walls of the tunnel range from 9.5 inches thick at the top, to 14 inches on the sides and bottom.

BUILDING MILE ROCK TUNNEL

The Mile Rock tunnel project was part of an engineering boom that occurred in San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake. The city attracted talented engineers to work on challenging problems, including Michael O’Shaughnessy. He was an experienced engineer with a thriving practice in Southern California, which he walked away from to become San Francisco’s City Engineer in 1912 at the age of 48.

In addition to spearheading many “smaller” municipal projects in the city like Mile Rock Tunnel during his tenure, O’Shaughnessy was best known for designing the Hetch Hetchy Water system.

Despite having the funds for Mile Rock Tunnel, it took some time to get the project off the ground. Originally scheduled to begin in 1910, Mile Rock Tunnel was delayed due to the city not obtaining right-of-way through the Sutro estate (or under the Sutro estate to be more accurate). O’Shaughnessy and Mayor James Rolph (1912-1931) eventually secured the rights a few years later.

Construction was estimated at $250,000 and began at both the southern and northern end of the tunnel. Piston drills, hand drills, and dynamite were used to bore through the solid rock and soil. Engineers and construction progress was so precise that when the two headings were jointed to form the final tunnel, there was less than a 1/4-inch discrepancy.

During the excavation of the open cut portion in 1915, looking north. Notice the billboards above.

Just over 900 feet of the tunnel was dug through solid rock, which was removed via narrow gage muck cars with mule traction, and transported by barge to the northern end of Ocean Beach, where it was used as fill. But you won’t see any of it today – a storm in early December 1915 washed most of the rocks and rubble away.

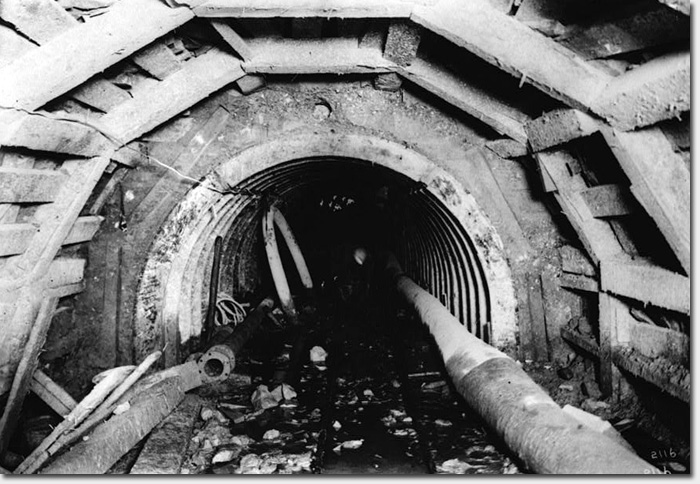

The parts that were not solid rock required timber support cribbing, which covered about 2,600 feet of the tunnel. It was the first tunnel in San Francisco to use a combination of open cut timber cribbing and boring through solid rock, considered a technological and engineering innovation at the time. Concrete and reinforced steel were also used in the construction.

Interior of the tunnel in 1915 during construction, showing the concrete lining and wood cribbing.

A turntable drilling rig with a 40 foot boom was also employed to excavate the tunnel. The rig could excavate about 200 yards per day near the surface, but only about 50 yards a day in the deeper parts of the tunnel where the rock was more solid.

On August 26, 1915, Mile Rock Tunnel was officially “inspected” by city officials and the press, including Mayor Rolph, City Engineer Michael O’Shaughnessy, head contractor Robert Muir, and the President of the Board of Public Works, Timothy Reardon.

The ceremonial inspection included the caravan of officials driving in a touring car from the south end of the tunnel to the north end outfall, where the incoming tide was held back with a temporary barrier. The drive was a great success, with the exception that they had to back the car all the way out of the tunnel.

The ceremonial inspection party that traveled by car through the tunnel. August 26, 1915.

After the ceremonial inspection, Mile Rock Tunnel was put into operation just a few days later, carrying storm water and sewage for the Sunset and West Mission districts and portions of the Richmond and Ingleside districts to the outfall at Mile Rock. Total cost for the construction of the tunnel was $218,617.47.

MILE ROCK TUNNEL TODAY

That was then and this is now, and dumping sewage into our oceans is no longer considered an acceptable practice for obvious reasons. Many of the outfalls across the city that dumped drainage in the bay or ocean were eventually closed off and new municipal projects like the Richmond Tunnel helped redistribute the flow.

Today, Mile Rock Tunnel is still in use but only for emergency overflow situations in the event of extreme weather.

In the late 1990s, a weir wall was constructed in the tunnel to prevent drainage from entering the tunnel. At the top of a weir wall is a small gap that does allow pass through, but only when levels are high due to extreme weather.

An example of extreme weather would be one inch of rainfall per hour for a consistent period of 3 hours. That kind of heavy rain would flood our sewer system and only then would the weir wall be breached, and drainage would enter into Mile Rock Tunnel, eventually flowing out into the ocean near Mile Rock Beach. We typically see this kind of weather about once or twice per winter.

Unlike its earlier career as an outfall for both storm water and sewage, today Mile Rock tunnel handles just storm water in the event of emergency overflow during severe weather.

The tunnel is permitted to handle a storm water to sewage ratio of 76:1 (76 parts storm water to 1 part sewage), but the realistic discharge is more like 100:1 or over 100,000:1, according to Dale Posey, the Superintendent of Oceanside Waste Water Treatment Plant. The system is designed to transport sewage off to the Oceanside plant for treatment.

While the original interior measured 9 feet high and 11 feet wide, years of sand flowing into the tunnel have narrowed it considerably. A report from 1995 estimated the height of the tunnel at 6 feet at the entrance and exit, but quickly narrowing to just 3 feet within 110 feet of the portals. You certainly couldn’t drive a 5 passenger touring car through that.

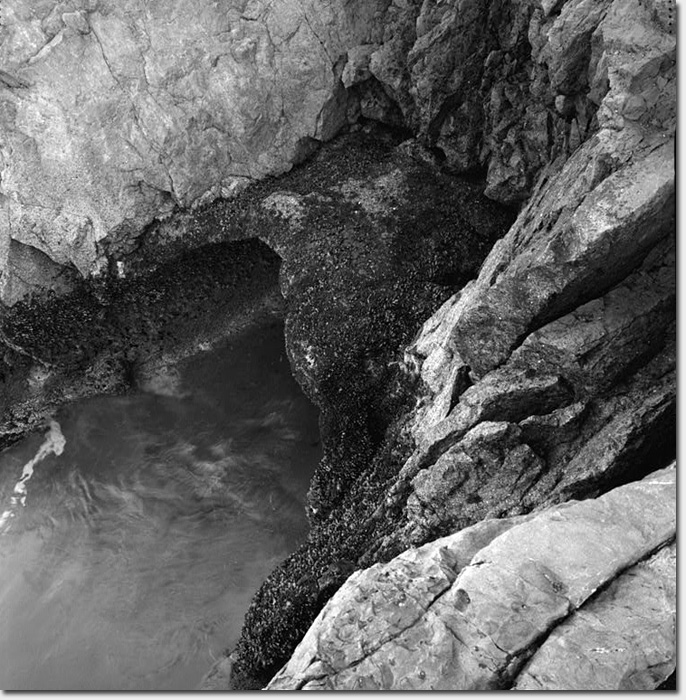

The only visible part of Mile Rock Tunnel today is the “manhole” near the outfall along the cliffs at Mile Rock Beach, which was designed like a smokestack. Its purpose is to provide air and access to the tunnel. There is also a small “gooseneck” vent that was installed along a walking trail on the west side of the Memorial parking lot above Lands End.

The manhole at the outflow near Mile Rock Beach. In 1994 at left, today at right. Someone call 311!

For more detailed information on the history of the tunnel and specifications on its construction, check out the Mile Rock Historic American Engineering Record from February 1995 (PDF). More historical photos of the tunnel, including larger sizes of the photos in this article, can be found at the Library of Congress online archive.

Special thanks to Richmond District historian John Freeman, Dale Posey of the Oceanside Waste Water Treatment Plant, and Greg Mayer of the SFPUC for providing information for this article.

Sarah B.

Plan and profile drawing of Mile Rock Tunnel, December 1913. View larger version

The manhole at the outflow near Mile Rock Beach

Looking down at the the outfall portal during low tide. 1995

FANTASTIC JOB, Sarah. Few people realize that you are not just an administrator of a neighborhood blog, who organizes stuff people send you. This article demonstrates that you are a FIRST CLASS journalist – doing the research and even finding and photographing what’s left above ground to see of the Mile Rock Tunnel. You’ve done a thorough job of “digging out the facts” (pun intended) on topic that few people knew about beyond a historic photo of the touring car in the tunnel.

CONGRATULATIONS on an intelligently written story that adds another piece to the intriguing history of the Richmond District.

Yes great story. Never knew there was such a tunnel.

Facinating, well written article about something I never realized existed. Thank you!

John, well said! Great article Sarah, thanks for doing this!

-Erin

Thanks for the article. I never knew about this either (and I am a professional historian who has done research and documentation on the SF water system – mostly on facilities outside the city though.) You added a new nugget to my knowledge!

Excellent Job, cool story!

OUTSTANDING!!! Great work Sarah! Just hope there aren’t any Morlocks skulking around down there ;^}

Great. I live three blocks from the southern terminus of this tunnel. Now I have to worry about C.H.U.D.S driving cars*?

* Yes, I read the article. I know there’s too much sand in there to drive a car through, but making the joke was more important.

Wow – I had no idea this existed! Love the history/informational posts about the ‘hood. Good stuff to know when we have visitors from out of town. Thanks!

Love the history posts! Thanks for writing and sharing.

Great article! Next you should write about the Alameda-Weehawken Burrito Tunnel.

http://idlewords.com/2007/04/the_alameda-weehawken_burrito_tunnel.htm

It would be great if you could provide a map or allow us better view of the posted map. I think i know where the gooseneck is– near the octogon house at land’s end– and always wondered what it is (I walk my dog nearly there nearly everyday). Is anyone allowed to go into the tunnel?

@Jonathan – Larger versions of all the photos can be found at:

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/search/?q=Photograph:%20ca1999&fi=number&op=PHRASE&va=exact&co=hh&st=gallery&sg=true

And no, the tunnel is not open to the public.

Sarah B.

The only question I have is where is the entrance? has it been covered up? I see nothing but houses on 48th and Cabrillo.

I’m guessing it starts at the sewers near Safeway, which means it all flows downhill (well, under the hill) to the bay, northward. Guessing drainage from Fulton flowed in a different direction.

@Gary – the “entrance” is underground, nothing you can lay eyes on. Check out the photo in the article that mentions the open cut excavation. You can sort of imagine how they would have built the approach to Sutro Hill, then bore into the mountain.

Sarah B.

OK thanks. I wonder if anyone has the fortitude to walk the length of that tunnel in the pitch black. Not if you have an active imagination.

Wow! Amazing facts about the neighborhood.

Like 😉

Nicely done, and a fascinating read that fills out well beyond the bits and pieces I knew before. Big hat tip from your neighbors at the Ocean Beach Bulletin. More!

Fascinating, well written. Emailed to everyone! Thanks Sarah!

Very cool article! Thanks!

I have been trying to figure this out – the tunnel starts near/at 48th and Cabrillo, is north/south in orientation, and ends up at Mile Rock Beach in San Francisco Bay? I can’t find Mile Rock Beach on a map, and I can’t figure out how this could end up at the bay?

Also, “There is also a small “gooseneck” vent that was installed along a walking trail on the west side of the Memorial parking lot above Lands End. ” Memorial Parking Lot? Can’t find it either, even though I know where Land’s End is.

My map does show a Seal Rocks State Beach, was Mile Rock renamed?

Thanks for any clarification!

@Erica – Mile Rock Beach is in the Lands End area. On this map, it’s just to the left of where Eagle Point Labyrinth is labeled:

http://goo.gl/maps/XQfKI

There are just over 200 steps down from the main Lands End trail to get to Mile Rock Beach. This video shows you what the beach is like once you’re down there:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YyejMKOEH8A

The manhole for the Mile Rock Tunnel outflow is further down the coast a bit toward the west.

The Memorial Parking Lot mentioned in the article refers to one above the Lands End Trail where there is memorial to the USS San Francisco—a WWII cruiser. You can see the memorial called out in this map, and near there is where the gooseneck vent is:

http://goo.gl/maps/w8EDF

So while this is not at all accurate in representing the actual route of the tunnel (there are turns in it), this gives you a general idea of where it starts and ends:

https://richmondsfblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/tunnel.jpg

Sarah B.

If you open Google Maps and follow a line north from 48th, you end up passing the parking lot on the east. Once you hit the water line you can see what looks like an unnatural notch cut out of the rock. I haven’t physically been down there but I think this is where the outfall portal is. If you follow the direction of that back toward land, you can just barely make out the stack with the graffiti on it. That area of google maps is kind a murky.

Plug these coordinates into Google Maps: 37.784537, -122.510115, then zoom all the way in and rotate the map so north is to the right. The green arrow is pointing at the stack.

Dear Sarah and MattyJ: You are both very kind to have responded so quickly, and with clickable links and maps and a video! It’s been a while since I was at Land’s End, and I’m happy to see all the work on the trails, and the labyrinth. I was able to get really close with your numbers, Matty, and could see exactly where the cut and the stack are.

I now know something about SF that I never knew before.

Do you both know about the water supply pipe from Ocean Beach all the way to downtown? For a club’s salt water baths.

Thanks again,

Erica

The coordinates above make sense. At about 37°47’0.05″N and 122°30’35.76″W is a gooseneck sticking structure out of the ground. I’ve walked by there a million times (really!) and wondered what that was. It’s in line with the coordinates above and 48th Ave, so it must be the gooseneck mentioned in the article.

the southern end is a few feet North of the intersection of 48th/ Cabrillo. Stand in the Northside crosswalk crossing 48th, face toward Sutro Hts. & a few steps in front of your feet there are 2 manhole covers. The rightside one, I guess, leads to the tunnel. I’d love to pop it open.

I’ve been mildly obsessed with thing for the past couple weeks. I made two attempts to get to the end of it and finally nearly succeeded this past weekend. It’s a fairly difficult hike over lots of rocks. We went at low tide on Saturday evening and there were still a lot of rocks to clamor over. By the time I got to the last big rock prior to the vent, it was already getting dark and I decided to turn back. Got a picture of it from about 40 yards away:

https://picasaweb.google.com/105142737944530674306/LandSEnd08182012#5778218439631646338

If you click the photo details on the right then click the map you can see exactly where I was when I took the photo. Look at the rest of the set for pictures of what you’ll have to go through to get down there. 🙂

The route we took started at the parking lot over Sutro Baths then headed toward the GG bridge on Land’s End Trail until we got to the stairs (269 of them) leading down to Mile Rock Beach. From the parking lot to the turn-off it’s about 3/4’s of a mile, but the trails are clearly marked. Just go down. Down. Down. Turn left at the water and head back toward Sutro Baths. Pay attention to your footing, you could easily break an ankle down there. And perhaps bring some snacks. It is not a leisurely stroll. 🙂