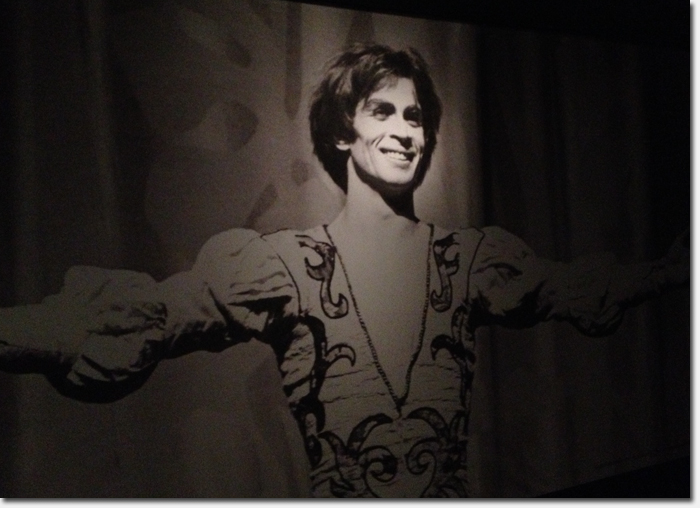

He knew from the age of 7 that dance was his destiny. And his sheer will, talent and determination drove Nureyev to become what many consider to be the world’s most famous male ballet dancer.

Ruldoph Nureyev: A Life in Dance is now open at the de Young Museum, showcasing the dancer’s prolific career through costumes, photos, video excerpts and small scale models.

Nureyev began his professional career at 17, when he entered The Kirov School in Leningrad in Russia. His impact was immediately felt, as he brought a new physicality to the stage and unlike his predecessors, took an interest in all aspects of the ballet, including the costumes.

By the age of 23, he was a superstar in his own country and when he defected from the Soviet Union during a trip to Paris in 1963, he became a worldwide sensation. What was once Russia’s national treasure was let loose on the Western ballet world to push boundaries and carve a new path for the modern male ballerina.

Nureyev was a perfectionist, and demanded the same focus, drive and dedication from all his collaborators. He had a particular passion for costumes, which he felt should not only be beautiful, but practical and able to keep up with the physical demands of his dancing. He enjoyed the flamboyance and creativity of costume design, resulting in embroidery, jewels and braid which can be seen throughout the exhibition.

While well preserved, many of Nureyev’s costumes in the exhibit belie the wear and tear of dozens of performances, where they were pushed to their limits and sweat-stained. The show features Nureyev’s costumes from some of his most famous performances including Swan Lake, The Nutcracker, Don Quixote, Sleeping Beauty and many others.

Costumes from Romeo and Juliet

“Nureyev was extremely precise and vigilant when it came to his own costumes, and he liked to have a qualified person attend the fittings so that he could bombard him with questions and benefit from his eye. He left the costumes for the rest of the dancers up to the designers, the production directors and the costume workshops. But his instructions were to be followed to the letter and his decisions final; no arguments were possible. If he saw that his indications had not been respected, he was capable of rejecting a whole series of costumes.” – from the Exhibition Catalogue for “Rudolph Nureyev: A Life In Dance”.

His love for costumes started as a young boy, when his sister Rosa would bring them home from her dance classes. Nureyev would spread them out on the bed, taking in every detail and nuance. “I was like a drug addict,” he said.

His obsession with costume even helped fuel his decision to defect from the USSR in 1963. After modifying his costume for a Paris performance with his Russian ballet company, Nureyev learned a few days later, at the airport, that he would be sent back to Moscow and not continue on with the company – effectively a punishment for the liberties he took with his role. Right then, he demanded political asylum in France.

Nureyev went onto become a worldwide celebrity – “dance’s first pop star” as some have called him. He was a regular on the 70’s nightclub scene, and was photographed as often as famous rock stars like Mick Jagger or John Lennon. He even appeared on The Muppet Show in 1977.

But Nureyev was first and foremost about dance, and he demanded absolute respect for it. “You live because you dance, you live as long as you dance” was his lifelong mantra. His career in dance covered all facets of it – choreography, dance, costume design – and included becoming Director of The Paris Opera Ballet in 1983.

Nureyev’s innovation resulted in the male ballerina taking on a more prominent role on the professional stage. Traditionally, the ballerina was always at the forefront on stage, but Nureyev’s aggressive strength and attention to visual costuming made the male roles more significant. He had that “it” factor and lit up every stage that he danced across.

“Nureyev’s work meant that men’s roles were no longer subservient to women’s. His unique combination of artistry, technical precision, electric stage presence, and musicality thoroughly transformed male dancing in the West,” said Jill D’Alessandro, the de Young’s curator of costume and textile arts.

If you have an interest in dance, ballet or just like to gaze on beautifully crafted costumes, don’t miss the Nureyev show at the de Young. It runs until February 17, and is included in the regular price of admission.

Sarah B.

“… the world’s most famous male ballerina.”

That might be appropriate for someone in drag, but men are most commonly called “danseurs” (a French term). If you want to stick to Italian, though, the term is “ballerino.”

I meant to include that the English “dancer” works perfectly well, too!

@Mike – Yes, good point. I changed it to be more appropriate. Thanks!

Sarah B.

Side note: Colum McCann recently wrote a fantastic novel that reimagines Nureyev through the eyes of those closest to him over 4 decades. Really wonderful writing, and it’s at the Richmond branch of the SFPL if you don’t want to spend money on it. It’s a nice companion, I think, to the exhibit.

Dancer: A Novel by Colum MCann

The video with “Miss Piggy” is a wonderful touch. A real tour de force of comedic ballet.