We’re pleased to share a new article from Richmond District historian John Freeman, who wrote this timely, drought-relevant article for the Western Neighborhoods Project. Enjoy!

Sarah B.

How Water Shaped Development of the Outside Lands

by John Freeman

San Francisco has unique geography. Over millennia of faulting, folding, uplifting and subsiding, the land surface at this end of the peninsula has a mixture of high peaks and low depressions, with a rock base and more than a third of it covered with dune sand. Beneath our western waters is sand from other geological developments south of us. The uplifting of the Sierra created rivers that moved millions of tons of glaciated sand westward across an inland sea, to exit the Coast Range at the Golden Gate, and deposit additional sand at our western edge. The sand bank shown on maps actually stretches under water all the way to the Farallon Islands. Tides, wind, and erosion contributed to the buildup of the sand throughout the north end of the San Francisco peninsula.

The shifting sand of this desert was the major deterrent to travel and homesteading, but the pioneers learned to cope in various ways. Large portions of the emerging city’s sand was moved into low spots or dumped into the tidal margins to create “made” land. The hills of San Francisco are a vital part of the development of the city. In earlier times, most of the steeper hills were impractical to build on because of the difficulty of access by horse and wagon, but also because there was no reliable water source atop the hills. As the city developed and pumping became feasible, many of the hills were used to create reservoirs for water from other sources to be stored for domestic use or fire protection.

Sand is a porous substance, allowing rainwater, even fog, to seep through it to the bedrock basin or aquifer. Before there was a reliable water system in San Francisco, wells were dug near the drainage of the hills to access that water. The topography of the Richmond and Sunset Districts is different, and these differences greatly affected their development. The Richmond District has a series of hills draining into it from three sides. The Sunset has primarily one hill system on its eastern flank, draining west toward the ocean and south toward Pine Lake and Lake Merced.

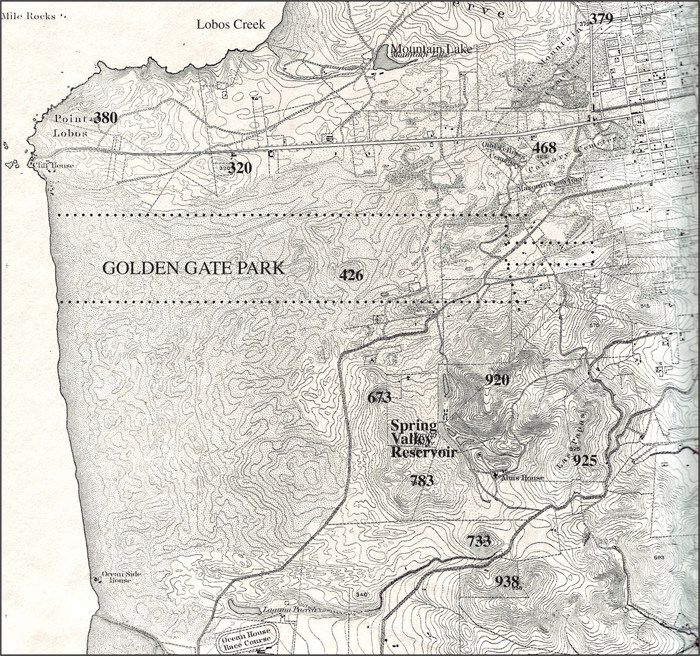

To best understand the original drainage system of the western portions of San Francisco where pioneers settled–the Richmond District, Golden Gate Park, and Sunset-Parkside areas today–we need to consult the major topographical map done by the United States Coast Survey of 1869. (See below.) This map was created before the street grid extended beyond the cemeteries or Golden Gate Park boundaries were drawn, but there are landmarks we can still reference today.

1869 United States Coast Survey Map with notes added – Courtesy of John Freeman

The 1869 map shows four major high points of land on the east of the southern side of the Great Sand Bank. The hill with an elevation 673 would be Grand View Park in Golden Gate Heights. South of that hill, marked 783, is the original elevation of Larsen Peak. Hill 733 is the original elevation of West Portal’s Edgehill Mountain, and lastly, hill 938, the highest elevation in San Francisco, is Mt. Davidson. Early development in the Sunset could be found at the base of these hills where water was available and near Pine Lake and Lake Merced. Water could be found fairly close to the surface back from Ocean Beach as well, but only near Golden Gate Park. A well in the middle of the current Sunset District would have to be drilled down through 400 feet of sand to reach the aquifer.

The topographical map reveals additional information about the drainage of these Sunset high-points. While they drain west and south, they also drain north through a narrow gorge, marked on the map as “Spring Valley Reservoir,” which was fed by the Sunset hills noted earlier, and the drainage of the west side of Twin Peaks (identified on the map as Las Papas and showing the south peak at 925 feet). Today this same reservoir site is at the intersection of Laguna Honda Boulevard and Clarendon Avenue. North of the reservoir can be seen a seasonal lake stretching to about Seventh Avenue and Moraga today. The map shows no surface river, but if you follow the contours north, another body of water appears, which is the low point of the botanical garden in Golden Gate Park, just north of Funston and Lincoln Way, where originally a lake and later pumping station used the water from that source to irrigate the park. The drainage continued through the park and into the Richmond District, terminating at Mountain Lake and Lobos Creek. Water from Lobos Creek was the city’s first domestic source, dating from 1858, when a redwood flume was built from the creek, before it reached the ocean at Baker Beach, around and through the Presidio to a pumping station at the foot of Van Ness Avenue. The water was then pumped up the north side of Russian Hill to two reservoirs, then to be piped to the city’s center…

Read the full article at outsidelands.org